Top: Mineworkers of an unidentified company have invaded the Bondi Mandingo Forest in Gbarpolu County. The DayLight/Esau J. Farr

By Esau J. Farr

GBARQUOITA – Illegal miners have encroached on a community forest in Gbarpolu County, felling trees, polluting streams and digging huge pits in their relentless mining for gold.

The miners set up a camp in the Bondi Mandingo Authorized Community Forest surrounded by large, deep pits, used as fences. The DayLight saw armed anti-riot police officers guarding the camp.

Asian mineworkers—based on their language and appearances—and others with a Ghanaian accent transferred gravels through excavators to a planting. The staffers interviewed corroborated the reporter’s observation of the miner’s nationalities. The miners arrived there last December, according to locals.

Our reporter photographed several trees felled by the company as well as large pits and dirt mounds. The miners have polluted the only creek in the area used by locals.

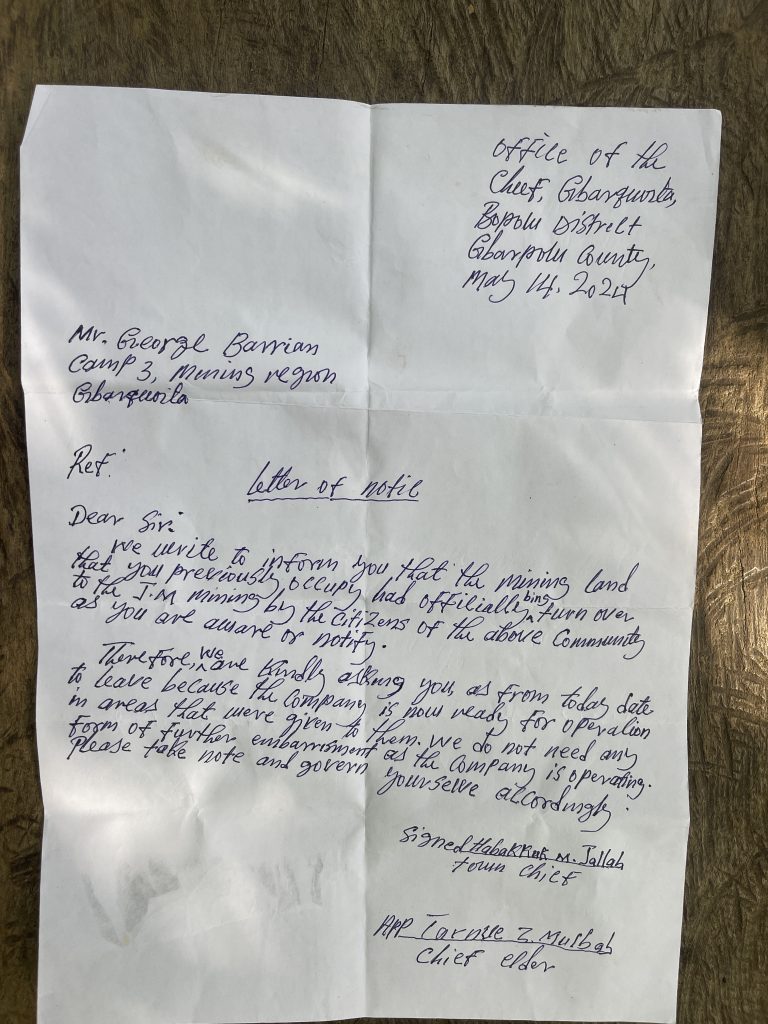

The name of the miner’s company is a mystery. It is called “JM Mining” in a letter from chiefs and elders, seen by The DayLight. A court document also refers to it as “Harming Mining Group of Companies.”

None of the two names are in the Ministry of Mines and Energy’s records. There are only three active, medium-scale mining licenses—consistent with the company’s operations—in Gbarpolu up to press time. None of the three licenses was granted for the area where the company operates.

Abraham Mulbah, a representative of the unidentified company, evaded several attempts for an interview. Mulbah had postponed an initial interview on the ground that he was visiting an ailing relative. He asked the reporter to meet him in Bopolu, promising to share copies of the mystery company’s documents. However, Mulbah did not turn out at the venue of the interview he had given.

Follow-up efforts the reporter made to get the documents failed, including connecting the newspaper with the company’s owners.

The mystery company signed an illegal memorandum of understanding (MoU) with locals of Gbarquoita to mine gold in the Kpo Mountain in early May this year, according to locals. They had arrived there for exploration in December last year.

Armed with the MoU, the company is forcibly buying local artisanal miners’ claims, assisted by chiefs and elders. Miners Fatu Quemue and George Berrian have all been asked to surrender their mining claims. Mulbah had shared their documents with The DayLight when the reporter tracked him down at the goldmine.

“We write to inform you that the mining land you previously [occupied] had officially been [turned] over to the J.M. Mining by the citizens of [Gbarquoita],” a letter from the community to Berrian read.

Berrain told The DayLight he accepted the proposal under duress, and he did not get the full amount the supposed company promised. “What I have on the land should be paid for.”

The DayLight obtained Quemue’s and Berrian’s documents, showing they were granted licenses. However, the ministry’s records show the pair have not surrendered or transferred their license for that area. Quemue’s license remains active. Berrian’s license is yet to be reactivated after renewal in April, a Liberia Revenue Authority receipt shows. Efforts to interview Quemue were unsuccessful, as The DayLight did not get her phone number.

‘Stupid’ and ‘Foolish’

Gbarquoita’s negotiation with the unidentified company violates the Community Rights Law… that created community forestry. The town is one of six that own the Bondi Mandingo Forest.

Bondi Mandingo was authorized by the Forestry Development Authority (FDA) in 2018. Covering 37,222 hectares, and has been under contract with Indo Africa Plantation Liberia Limited ever since. However, the Singaporean loggers abandoned the contract.

Gbarquoita is exploiting the contract’s failure with the signing of the MoU—unapologetically.

“We are happy because we have been suffering for long,” said Habakkuk Jallah, the Town Chief of Gbarpquoita.

“Since the government of Liberia built a clinic for us over five to six years ago, there have not been medicines at the clinic. The company is now going to put medicine there…,” Jallah added. He said the MoU with the miners mandates them to provide hand pumps and 150 solar lights. Efforts to get the MoU did not materialize.

But the Community Rights Law does not give the Gbarquoita the right to unilaterally negotiate a contract. That power solely lies in the hands of Bondi Mandingo’s community forest management body (CFMB).

Mark Dennis, the chief officer of the CFMB, told The DayLight the company prevented them from entering the forest.

“We made our way through there to see the level of destruction that was done,” Dennis said of the February incident. “When we got there, they chased us [out] with their machine.”

Not long after his ordeal, the leadership of the Bondi Mandingo sued the illegal miners. The lawsuit alleges the miners threatened to “teach” Dennis and co “a lesson,” calling them “stupid” and “foolish.”

Charges the miners face include criminal trespass, criminal mischief and disorderly conduct, filings of the Bopolu City Magisterial Court show.

The lawsuit requests US$500,000 for alleged damages to forest resources. It cites one Isaac and another man only identified as Sao and all of the company’s operators as defendants.

The men were arrested but released on bail, according to court records.

The case commences on Wednesday.

The United States Embassy in Monrovia funded this story. The DayLight maintained editorial independence over the story’s content.