Top: Representative Thomas Romeo Quioh of Sinoe County’s Electoral District-1 sits next to an executive of African Finch Logging Limited, a company whose board of directors he admits to being on. Picture credit/Anonymous

By Varney Kamara

MONROVIA – Representative Thomas Romeo Quioh of Sinoe County’s Electoral District-1 has admitted his connection to a shady logging company, while denying it.

Quioh was reacting to a recent DayLight investigation, citing allegations by locals that he co-owned African Finch Logging Limited, a UAE-based firm that has a logging MoU with the Numopoh Community Forest in Sinoe’s Kpayan District. Locals, including county officials, accused Quioh of bribing and intimidating chiefs and elders into signing the document the same day he introduced it.

“As a duly elected lawmaker and a member of the advisory board of directors of the African Finch…, my involvement in forestry-related matters is strictly in the confines of legislative oversight,” Quioh said in a Facebook post last Thursday.

“My position on the advisory board of the forest management committee of the district and a non-voting member of the advisory board of the African Finch…,” Quioh added. He followed up that post with a press conference on Friday.

Quioh’s confession to his African Finch role confirms at least one of the allegations locals made. The investigation cited people who accused the lawmaker of co-owning the company, based on his part in the deal.

By his admission, Quioh is liable for multiple conflicts of interest. First, as a representative, he is a statutory member of Numopoh’s forest leadership. Also, as a lawmaker, he has oversight over the Forestry Development Authority (FDA), which governs the logging sector.

This means that Quioh is caught between performing his duties as a lawmaker and his responsibilities as the director of African Finch’s board.

The Code of Conduct for Public Officials prohibits such conflicts of interest. “No Public official or employee of government should use an official position to pursue private interests that may result in a conflict of interest,” it says. Breaking the code constitutes a penalty, including a reprimand, a fine, or removal from office.

Quioh’s conflicts of interest nullify Numopoh’s contract with African Finch. The National Forestry Reform Law bars Quioh and other officials from playing such a role in a private company. It bars “a person associated through investment, ownership, effective control, or other similar means.”

Board of directors

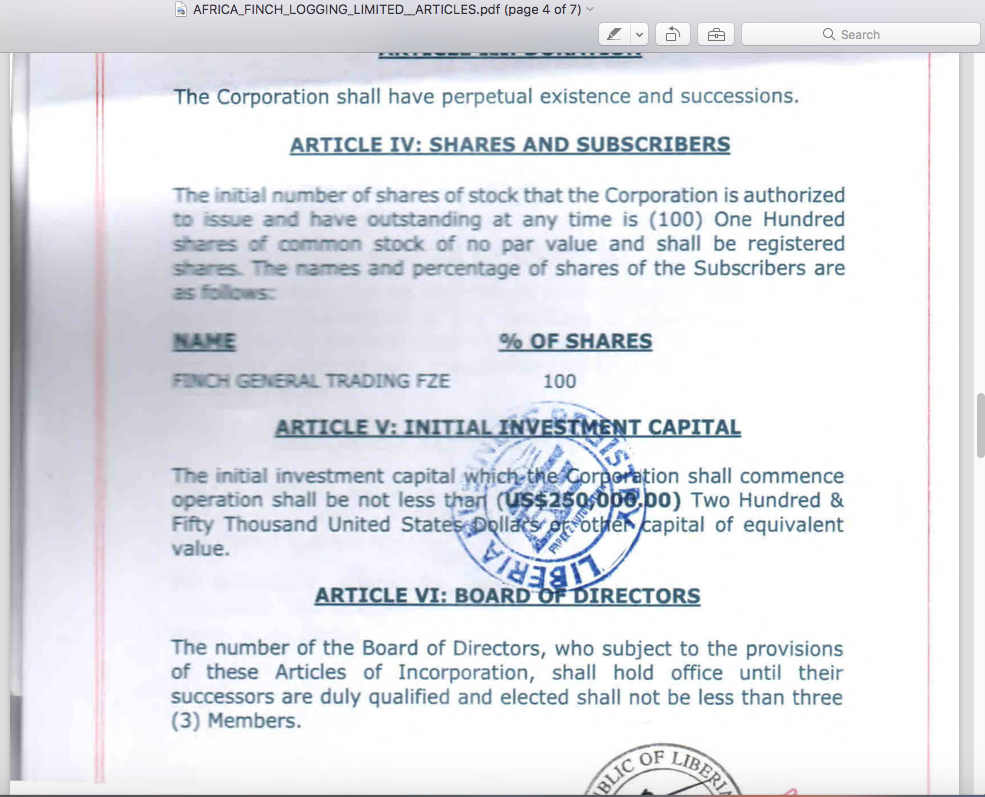

African Finch’s article of incorporation shows it is a subsidiary of Finch General Trading Limited FZE, another UAE-based company. However, the article does not show the persons who own African Finch or Finch General, a violation of the Beneficial Ownership Regulation. The regulation requires companies to declare their human owners, not just parent companies.

Such shadowy ownership neither denies nor confirms the locals’ allegation that Quioh co-owns the company, The DayLight reported.

Kwadjo Asabre, an African Finch executive, fueled the local people’s allegation. When contacted for the company’s side of the story, Asabre told this reporter to “Speak to [the] Hon.”

Quioh appears to lessen his role in African Finch by falsely suggesting it has an advisory board, instead of a board of directors.

A board of directors differs sharply from an advisory board, according to Black’s Law Dictionary, a leading global reference for legal definitions. A board of directors is a governing body that supervises a company’s activities with legally binding decisions. In contrast, an advisory board provides expert advice and recommendations that are not legally binding.

Accordingly, Quioh plays a much crucial role in African Finch than he has admitted. This likely explains why Asabre referred this reporter to a lawmaker when the newspaper sought an interview with the company.

Quioh claims the newspaper published its story “without [a] proper engagement with his office.” However, the evidence contradicts that claim. The DayLight did contact Quioh and published its article nearly a month later.

On March 20, DayLight reached out to Quioh via WhatsApp with its queries. The next day, in a phone interview, Quioh failed to respond to the queries. Instead, he boasted about his wartime logging experience, ranting at this reporter and hanging up the phone.

“You cannot teach me forestry. You don’t know me. I am one of the longest-serving foresters in this country,” said Quioh, who served as an FDA deputy managing director during Liberia’s deadly civil conflict. He continued the bragging in his press conference and WhatsApp messages to the newspaper.

But wartime foresters are not glorified as Quioh suggests, as they are synonymous with forestry’s darkest era. Logging companies used timber resources to fund warring factions, including forces loyal to the Liberian government. Thus, the phrases “blood timber” and conflict timber” were born, leading to United Nations sanctions in 2003. The sanctions were lifted following rigorous reforms that partially bar wartime loggers from conducting any forestry activities. However, the provision is not being enforced.

Facebook Comments