Top: Mr. Augustine B.M. Johnson on the Liberian delegation at the just-ended climate change conference in Baku, Azerbaijan. Facebook/Augustine B.M. Johnson

By Emmanuel Sherman

WHEIN TOWN—The Forestry Development Authority (FDA) has rehired a former manager who was disgraced on multiple occasions for alleged corruption and involved with companies punished for logging offenses.

The FDA hired Augustine B.M. Johnson as a consultant in June. He gets US$2,500 as a service fee, US$300 for fuel, and US$100 for communication, according to a document obtained by The Daylight. Johnson’s duties include assisting with forest management planning, supporting compliance, and advising on forest mapping. He represented Liberia at the United Nations climate summit in Baku, Azerbaijan.

But, Johnson’s roles starkly contradict his reputation at the FDA, where he served as the geoinformation system manager in the 2000s and 2010s. Johnson was found liable in the Carbon Harvesting Corporation (CHC) and Private Use Permit Scandals, forestry’s biggest postwar controversies. Later, he managed West African Forestry Development Inc. (WAFDI) and Mandra Forestry Liberia Limited, two of forestry’s dirtiest.

Before his rehiring, Johnson was touted as the FDA’s Deputy Managing Director for Technical Affairs but eventually lost the position to Gertrude Nyaley, a former director of the agency’s legality verification department.

Criminal carbon contract

In 2010, Johnson and other officials fraudulently attempted to award a carbon contract to the London-based CHC for 400,000 hectares in River Cess County. Had it gone through, experts said Liberia would have a US$2 billion loss.

An official inquest found that Johnson introduced himself as a “resident expert,” allegedly receiving a bribe and computer from CHC. He then conducted a so-called biomass study on four plots of land in the southcentral county and tried to deceive the Office of the Prince of Wales about the “groundbreaking” deal.

“Johnson and colleague provided confidential information about the FDA to CHC and allowed CHC to draft the FDA document that they would have [then-Managing Director John Woods] and other FDA officials sign,” investigators said.

Investigators recommended Johnson’s dismissal and subsequent prosecution, which President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf—his relative—accepted but later rescinded.

Forgery

In 2012, two years after CHC, Johnson participated in the infamous PUP Scandal in which the FDA illegally awarded about 2.5 million hectares of forests to logging companies. It remains the biggest postwar logging scandal.

An official investigation found Johnson illegally received money for boundary line demarcations and verification fieldworks. Investigators established his report for those events was falsified in “many cases” and inconsistent with a private use permit, awarded solely for private land. A Liberia Land Authority review showed 57 of 59 permits unlawfully involved community lands, supported by fraudulent documentation.

It turns out, that most of the forestlands Johnson and other FDA technical staff had issued had overlapped proposed protected and logging concession areas.

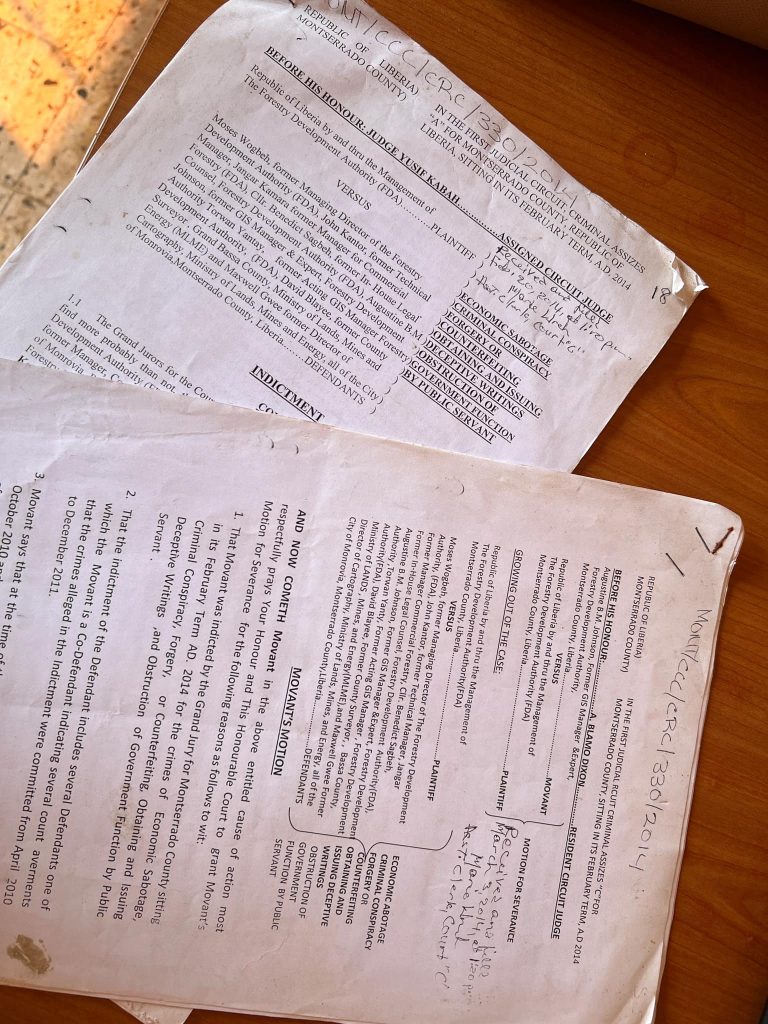

Unlike the CHC scandal, this time around, Johnson, then-FDA Managing Director Moses Wogbeh, and several officials were prosecuted. Wogbeh and others were found guilty of economic sabotage, criminal conspiracy, and other crimes but filed an appeal with the Supreme Court. The case still lingers at the high court. Criminal Court ‘C’ had granted Johnson’s petition for a separate trial, which never happened.

Johnson denied any wrongdoing regarding the CHC and PUP scandals but declined an interview with The DayLight for this story.

Illegal Logging

Illegalities followed Johnson from the FDA to WAFDI. A 2021 Ministry of Justice investigation found that West African Forest Development Incorporated (WAFDI) illegally harvested logs in Grand Bassa County’s Compound Number Two. The FDA had incorrectly awarded the company 14,460 hectares of extra woodland in the Gheegbarn #1 Community Forest. WAFDI exploited the error for three years, exporting a huge volume of logs at the hand of the process.

Following the investigation, the Ministry of Justice reprimanded the FDA and WAFDI for the irregularities. Accordingly, WAFDI’s operations were suspended for nearly a year. “WAFDI is an operator in the forestry sector, they are also obligated to know and comply with all forestry laws and procedures…,” wrote then-Minister Musa Dean.

Abandoned logs

Amid WAFDI’s rebuke, Mandra—Johnson’s other company—was being punished. The FDA suspended Mandra’s harvesting certificates and two other companies for not enrolling their logs into the FDA log-tracking system and abandoning logs in Sinoe County. A DayLight investigation found the company abandoned some 7,000 logs from the Sewacajua Community Forest, the single-most ever reported.

In a phone interview last year, Johnson appeared unfamiliar with the Regulation on Abandoned Logs…, one of the instruments he has been consulted to enforce.

He claimed that paying the fees on a log prevented its abandonment. “Before you talk about abandonment, I am expecting a ship to come to Greenville by the second week of next month to get the logs out,” Johnson said in the interview.

His comments contradicted the 2017 regulation, which defines abandonment as logs left unattended between three weeks and six months, depending on their location.

Conflict of Interest

Johnson’s well-documented activities and his current role at the FDA are a conflict of interest. Apart from WAFDI and Mandra, he has been linked to joint ventures with the Liberia Tree and Timber Company and the EJ&J Logging involving two large-scale forest concessions.

In June, Johnson represented logging companies at an annual meeting on a timber trade agreement between Liberia and the European Union. He even made remarks on behalf of commercial loggers, the third week into his second spell at the FDA.

In a letter last week, the NGO Coalition of Liberia urged President Joseph Boakai to address Johnson’s conflict of interest.

“Allowing individuals with such vested interests to influence forest governance undermines the integrity of the FDA and Liberia’s commitment to transparency and good governance,” the NGOs wrote. The Executive Mansion did not immediately respond to The DayLight queries.

Similarly, the FDA’s Managing Director Rudolph Merab did not return questions for comments on Johnson and the other issues. However, Merab’s appointment to the FDA follows the same pattern as Johnson’s return to the regulator. Like Johnson, Merab is a serial illegal logger, having himself participated in the PUP Scandal and wartime logging operations.

This story was a production of the Community of Forests and Environmental Journalists of Liberia (CoFEJ).