Top: A pit dug by Urban and Rural Services Inc. in Todee, Montserrado County. The DayLight/Esau J. Farr

By Esau J. Farr

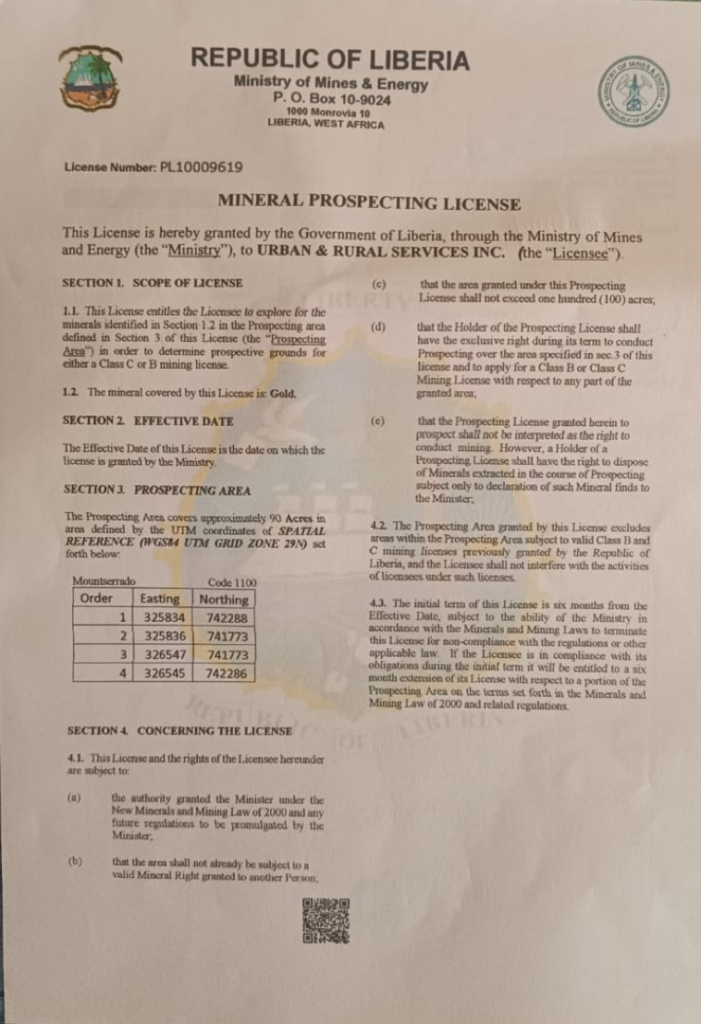

- The Ministry of Mines and Energy awarded a company a fake license whose information matches that of an expired license in a bid to cover up an illegal memorandum of understanding (MoU) between the company and Todee District

- Montserrado lawmaker Lawrence Morris and Superintendent Florence Brandy signed the illegal MoU, carved on a paper with the letterhead of the National Legislature

- Urban and Rural Services Inc. did not have a mining license before signing the five-year MoU, in which it agreed to pay the community an estimated US$41,000 to mine in the mineral-potential region

- This investigation exposed how the Ministry of Mines in the past unlawfully awarded the company licenses nearly six times above what it paid for and three times the legal limits

MONROVIA –The Ministry of Mines and Energy has used a fake license in an apparent attempt to justify an illegal Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between a mining company and Todee District, which Representative Lawrence Morris and Superintendent Florence Brandy of Montserrado endorsed.

The February 1 MoU, written on a paper with the letterhead of the National Legislature, sanctioned the company to mine on 90.18 acres of land in the Ding-Gola Chiefdom, according to the document.

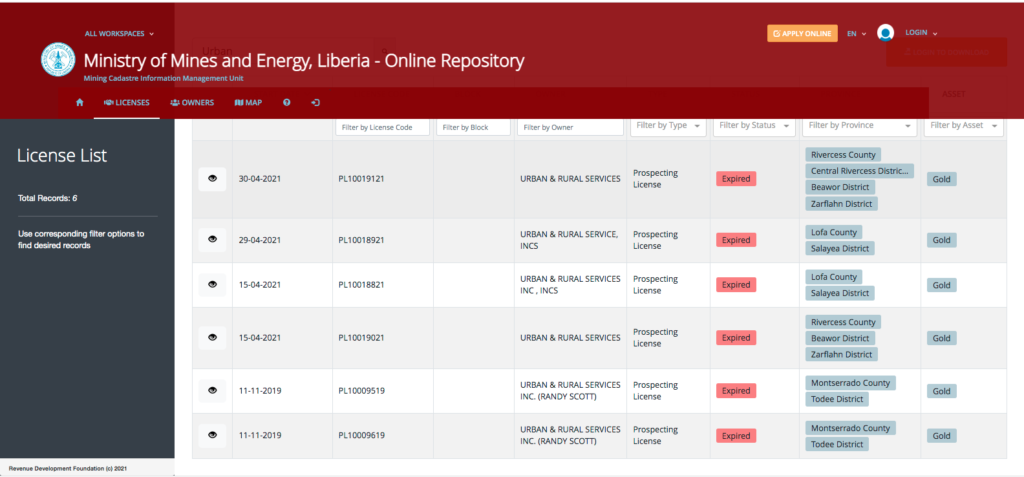

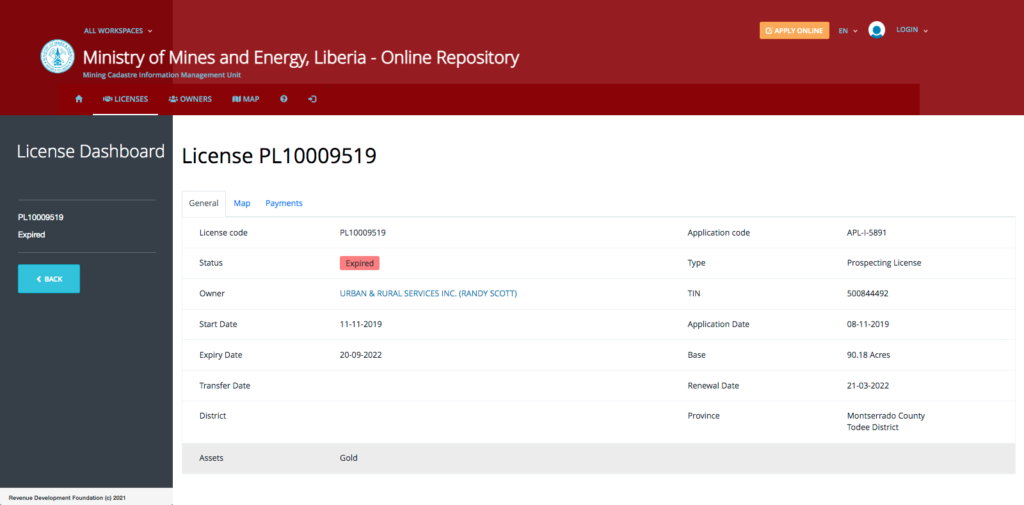

In April, an investigation by The DayLight found out that Urban and Rural Services Inc., owned by one Prince Nah, did not have a valid mining license prior to the signing of the MoU. All six of the company’s licenses have expired and remained so up to press time. Mining without a license is a violation of the Minerals and Mining Law, punishable by not more than US$2,000 or up to 24 months of imprisonment, or both the fine and prison term, upon trial.

But in an apparent attempt to cover up the illegal MoU and clear the names of Representative Morris, Superintendent Brandy and Urban of wrongdoing, the ministry issued the company a fake license.

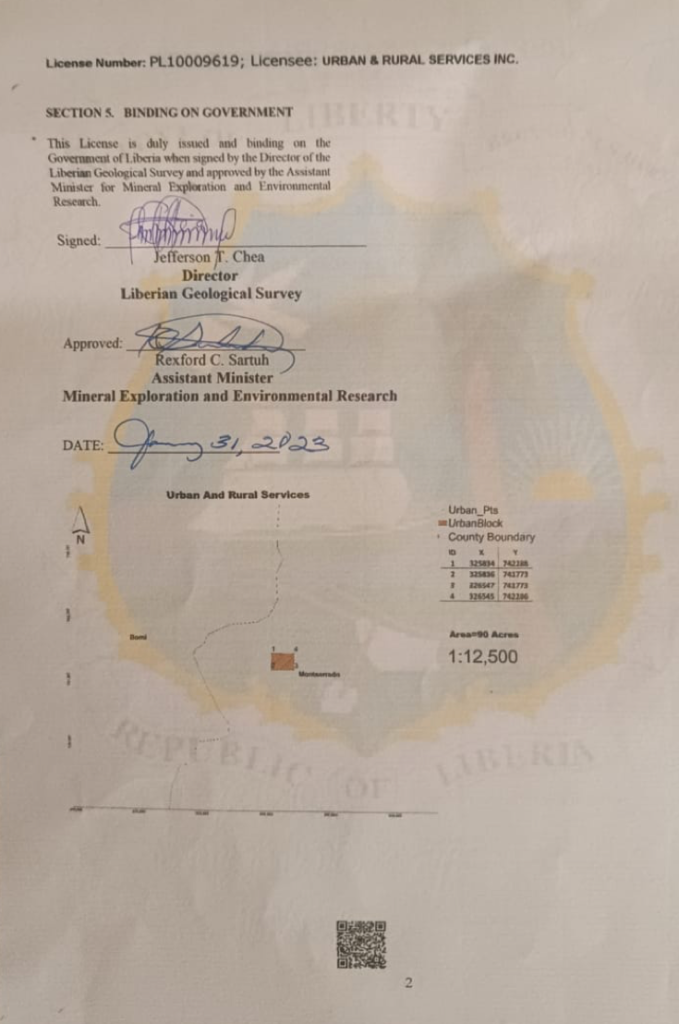

The bogus prospecting license was purportedly issued on January 31 by the Assistant Minister for Mineral Exploration and Environmental Research, Rexford Sartuh, and Director of the Liberia Geological Survey, Jefferson Chea.

“The license is hereby granted by the government of Liberia, through the Ministry of Mines and Energy… to Urban and Rural Services…,” the falsified document read. “This license entitles the licensee to explore for minerals identified… in the prospecting area…”

The document, obtained by The DayLight, bears the code of an expired license Urban held between 2019 and 2021 to prospect for gold in Todee, according to official records.

The fake license’s geographical positioning system (GPS) points also match those of the expired document. This literally means Sartuh authorized Urban to dig in the same pit it prospected between 2019 and 2021, which is unlawful.

A search on the ministry’s online repository—a landmark tool that enhances transparency and accountability—using the code will take you to the expired license, not the fake one. There is no trace of the fake one there. (Every license has a unique code.) Even the Liberia Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (LEITI) captured the expired license in its 2020-2021 report with the license code.

Forging a mining license is a violation of the mining law. It requires violators to pay US$1,000 or US$2,000, or between spend two or three months in prison after conviction.

People in Todee were aware that Urban did not have an active license when it signed the MoU. Some distanced themselves from it, including Bendu Kotoe, a women’s leader in Ding Clan, which hosts the Kponneh Mountain.

“The mining license they are supposed to bring, we have not seen it yet. So, we don’t agree for them to work,” said Kotoe back in March.

Mohammed Sheriff, a representative of Urban, conceded its MoU and operations were illegal, and that they were working to correct their wrongdoing.

“Recently, we had a guest from the Ministry of Mine and Energy, I think a regional agent,” Sheriff told The DayLight in an interview. “He advised us to have a legal license to avoid future embarrassment with authorities, and myself I agreed with him.” Sheriff, who did not identify the regional officer, echoed that in a follow-up interview on Monday, almost two months after he last spoke with this reporter.

Cooper Vooker Pency, the Director of the Cadastre Information Management Unit, confirmed Urban did not have a license. Pency supervises the processing of applications for mining management of licenses throughout its lifespan.

The DayLight had raised a qualm in an email to Pency that Urban’s licenses were not visible on the repository. Pency then sent a screenshot of Urban’s expired licenses, including the one whose details Sartuh had forged. Pency reset the repository to allow Urban’s expired licenses to reflect. “Expired and other categories of licenses have been added to the repository,” Pency said in his reply to The DayLight.

While the details of the prospecting license match the information of Urban’s expired license, both documents are inconsistent with the illegal MoU. The MoU is for five years, 10 times the lifespan of the fake prospecting license Sartuh issued and consistent with a class B license.

The cost of a prospecting license and the value of the MoU are other issues. Urban is due to pay the community almost ten times the fee for a prospecting license: US$125. It must pay Todee US$1,000 annually and L$100,000 monthly to affected communities, based on the MoU. That is an estimated US$41,000 over the five-year period, according to The DayLight’s calculations. In fact, Urban has already paid for a month as of March 29, according to residents and Sheriff.

Urban’s license and payment history seemingly pinpoints it is evading taxes. All six of the expired licenses were prospecting licenses. Normally, after prospecting, companies obtain either an artisanal mining or class C license or a class B mining license. These licenses are costlier than a prospecting license, with class C costing US$150 and class B US$10,000.

It appears Urban was hiding behind a prospecting license while it engaged in class B mining activities in Todee. Pieces of equipment this reporter photographed suggest the company had been mining in the area, not just researching. This reporter photographed an improvised device used to wash gold, commonly called kata-kata machine. There were also earthmovers and other equipment, and the company has already reset up a camp in the area and paved roads. Todee is part of a region geologists say has the highest potential for the minerals in Liberia. Its rock—important for mineral formation—are some of the oldest in the country and the Mano River region.

Overstayed Licenses

The DayLight’s review of LRA records revealed shocking details. The two prospecting licenses Urban has held in Todee lasted for three years. As the one Sartuh forged, the other license was also awarded in 2019 and expired in 2022, official records show. That is another violation of the mining law, which limits the lifespan of a prospecting license to at most one year.

Our review also revealed that Urban only paid for four of its six initial prospecting licenses. That is a revenue loss of about US$1,750, according to our calculation, taking into consideration the extension of the old licenses and the acquisition of new ones.

Urban actually paid US$125 for a new prospecting license on January 24 this year, according to the LRA. However, that license has not been awarded, as it is still being validated, based on the ministry’s records.

It was unclear whether Urban declared any volume of gold as the law mandates. Its production is not captured in the LEITI report neither does the LRA record show it paid any royalties on the export of gold. Illicit mining reduces the government’s revenue by millions, according to a 2021 report by the General Auditing Commission (GAC).

Randy Scott, an executive of the company, denies any wrongdoing amid the plentiful pieces of evidence. Scott argued that he was not the one who issued the license and therefore he should not be held liable for any violations.

Asked why Urban held the prospecting licenses for more than one year, he blamed it on the coronavirus pandemic. “When did the government stop people from mining here?” Scott said. “You were not here during the COVID-19 period?

But Scott’s points are not backed by facts. First, the government did not halt mining processes across the country. And prospecting licenses the ministry issued during the same time Urban’s, including in the very Todee, lasted for exactly six months.

For his part, Representative Morris previously said he put the MoU on his office’s letterhead to give it credibility, and that he wanted to be held responsible for any outcome of the document.

Later in the interview, he said he had thought the MoU was for exploration, not for mining. His statement is not backed by facts, as the MoU clearly authorizes Urban to “carry out gold mining activities.”

“I do not work for the [Ministry of] Mines and Energy, and if I had not done my due diligence…, I wouldn’t have gone forward,” Morris said via WhatsApp. “How am I supposed to know a fake license from a real one?”

Sartuh and Chea did not respond to emails, text messages, and phone calls in two weeks for comments. Chea failed to grant an interview, despite promising on two occasions. He did not also return WhatsApp and text messages.

Meanwhile, Residents of Todee have threatened to protest over Urban’s alleged mining in a river there, according to the Liberia Broadcasting System. They have given the company a two-week ultimatum to halt all dredging activities, which are banned in Liberia.

Funding for this story was provided by the Green Livelihood Alliance (GLA 2.0) through the Sustainable Development Institute (SDI). The DayLight maintained complete editorial independence over the story’s content.

Facebook Comments